In 1929, thousands of Igbo women gathered outside a colonial office in southeastern Nigeria.

They sang. They danced. They composed sharp, mocking songs about the British officials who had begun taxing their families.

Then they occupied the buildings.

Colonial records dismissed it as a riot.

History remembers it differently.

Nearly a century later, women in Zimbabwe march through Harare holding placards that read “Freedom cannot exclude women.” Some are arrested. Some are beaten. Most return to the streets anyway.

From the markets of Aba to the townships of Bulawayo, African women have been resisting power for generations. The question is not whether feminism is African. The question is why their resistance is so often forgotten.

Nigeria: Resistance Before and After Colonial Rule

In Nigeria, women’s resistance has deep roots.

Before British rule, many communities allowed women to trade independently, influence local councils, and organise collectively. Market associations were powerful. Women controlled supply chains. Some held titles that carried real authority.

Colonial administration changed that balance.

British officials recognised men as household heads. They centralised power in male-dominated warrant chiefs. They imposed taxation systems that ignored women’s economic roles. Land ownership and political participation increasingly passed through men.

The legacy of colonialism did not only redraw borders. It reshaped how African societies treated women.

In 1929, that tension exploded.

Thousands of Igbo women mobilised against new tax measures that threatened their livelihoods. They used traditional protest methods, including surrounding officials, singing satirical songs, and publicly shaming those in authority. It was organised. It was strategic. It spread across towns.

Colonial officers opened fire. Dozens of women were killed.

The protests forced the British administration to review its policies and reform aspects of local governance. More importantly, they demonstrated that women were not passive subjects of empire. They were political actors.

Women who took part in the Aba Women’s War of 1929 challenged British taxation policies. Photograph by Laurie Bloomfield, press photographer for Durban’s Daily News. Taken on 17 June 1959.

Zimbabwe: Liberation and Its Limits

Zimbabwe tells a similar story, though in a different era.

During the Second Chimurenga from 1966 to 1979, women did far more than support from the sidelines. Some joined guerrilla units. Others transported supplies, carried intelligence, sheltered fighters, and mobilised rural communities. Spirit mediums invoked ancestral authority to legitimise the struggle.

Under white minority rule, land dispossession and forced labour fractured families. Men migrated for work. Women managed households under tightening restrictions. Many concluded that liberation required their direct participation.

When independence came in 1980, images of unity filled the streets.

But independence did not automatically translate into equality.

Independent governments promised change. For many women, that promise is still waiting to be kept.

Political leadership remained largely male. Access to land and economic resources continued to favour men. Women were praised as “mothers of the nation,” a phrase that sounded respectful but also carried a message: nurture the country, do not lead it.

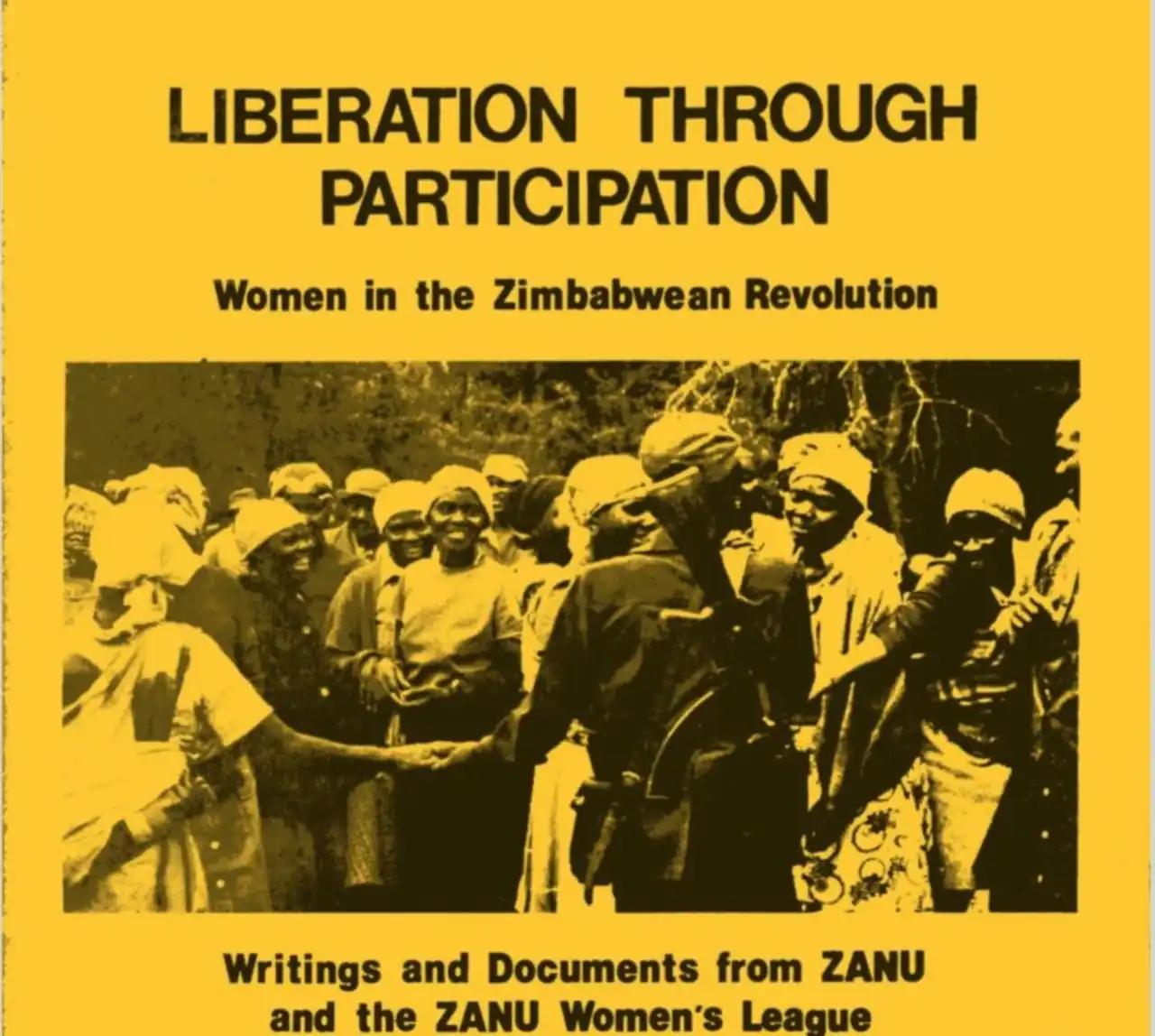

Women in Zimbabwe’s Liberation Struggle

Women participated directly in Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle, serving as fighters. [Image Credit: contemporaryand.com]

The Struggle Continues

The pattern is not confined to history books.

In recent years, Nigerian women have been visible in movements such as #BringBackOurGirls and #EndSARS. Zimbabwean groups like Women of Zimbabwe Arise (WOZA) have organised peaceful protests demanding constitutional rights, economic reform, and protection from abuse.

They face arrests. They face intimidation. Yet they continue.

What connects these movements is not imported ideology. It is lived experience.

Economic hardship affects women directly when markets collapse or food prices rise. Political instability affects them when public services fail. Violence, whether domestic or state-sponsored, often lands first on women’s bodies.

To call their activism “un-African” ignores this history.

African women have never waited quietly for change. They have negotiated power within families, markets, churches, farms, and liberation movements. Sometimes they have done so within cultural frameworks. Sometimes they have confronted those frameworks directly.

Their strategies have varied.

In Aba, songs and collective shaming became tools of pressure. During the Chimurenga, armed struggle and rural networks carried the message. Today, smartphones amplify voices once confined to local meetings.

Different methods. Same insistence on dignity.

Contemporary women activists in Zimbabwe and Nigeria continue a long tradition of organised resistance. [Image Credit: Zinyange Auntony / AFP via Getty Images.]

The Unfinished Conversation

There is another uncomfortable truth.

After liberation struggles end, women are often told that unity must come first and gender concerns later. Criticism is framed as disloyal. Demands for reform are labelled foreign influence.

This narrative is convenient. It shifts attention away from unfinished business.

The legacy of colonial rule disrupted economic systems and reinforced male dominance in new ways. Post-independence politics did not fully undo those patterns. In some cases, it reproduced them.

Land reform debates in Zimbabwe, representation gaps in Nigerian politics, wage inequality, and gender-based violence are not isolated issues. They are part of a longer story about who is allowed to shape national direction.

When a young woman in Harare speaks about harassment online, she is not importing an idea. She is continuing a conversation her grandmothers began in markets and villages decades ago.

When Nigerian women organise around police brutality or school kidnappings, they are drawing on networks that once challenged colonial tax collectors.

The forms change. The demand remains constant.

Recognition. Safety. Voice.

So is feminism un-African?

If by feminism we mean the belief that women deserve full participation in political, economic, and social life, then the historical record suggests the opposite. From Aba to the battlefields of the Chimurenga to present-day protest movements, African women have insisted on that principle long before it was packaged in academic language.

The story is not about importing ideas. It is about acknowledging contributions.

History did not begin with hashtags. It began with women who refused silence.

Their struggle did not end with independence. And it is not over now.

About the Authors

Ebenezer Jakaza and Moses Danjuma are first-year students in International Relations and Diplomacy at Africa University.

Flipcash is Your Trusted PayPal & Crypto Exchange Partner in Zimbabwe — WhatsApp +263 77 163 9263

The post Is Feminism Really ‘Un-African’? Lessons from Nigeria and Zimbabwe appeared first on iHarare News.